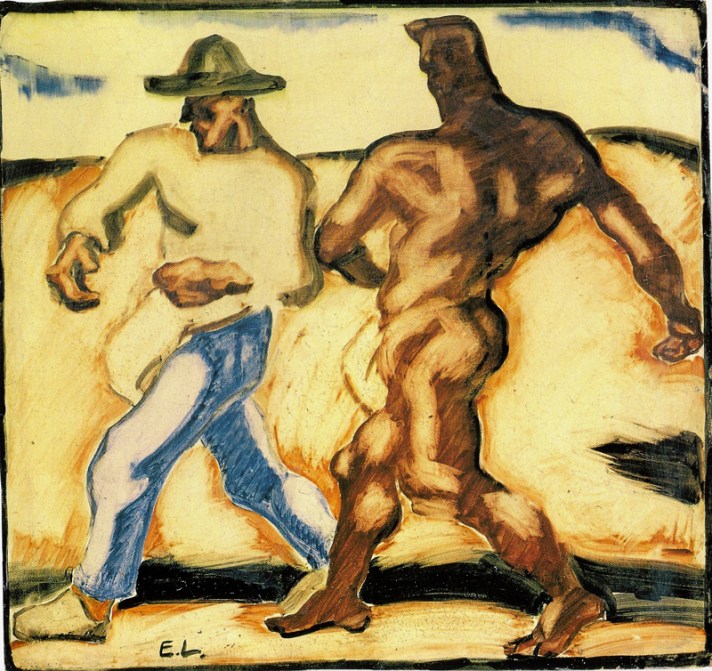

Egger-Lienz, Albin, 1868-1926. Sower and the Devil, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=55000 [retrieved July 24, 2023]. Original source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Egger-Lienz_-_S%C3%A4hmann_und_Teufel.jpg.

RCL Year A, Proper 11 (Alternate Readings

Isaiah 44:6-8, Psalm 86:11-17, Romans 8:12-25, Saint Matthew 13:24-30 and 36-43

Last Sunday, at least once, I allowed that the Parable of the Sower is scary, because three of the four scatterings of seed fail to produce fruit. One of the four scatterings, only, produces fruit. One of the four succeeds as a crop. It seems scary to me that one out of four would be acceptable to God, for God has a purpose for everything that is. The three scatterings of seed that produce no crop, do they have any purpose whatsoever?

But the parable today, once known as the Parable of the Wheat and the Tares, can be equally, if not more scary, because of what we may be tempted to do as the Wheat and the Weeds grow together.

“The field is the world,”[1] Jesus says in his interpretation of the parable now known as the Parable of the Wheat and the Weeds. Could he have possibly foreseen the world in which we live in the twenty-first century?

We have perceived the world in such a way that we see it sharply divided, like the field in the parable, between the wheat and the weeds. We have legal and illegal people, we have Democrats and Republicans, we have haves and have-nots, we have rich and poor, we have capitalists and communists, we have the insured and the uninsured, and we have Christians and Jews on one hand, and Islamists on the other. Some time ago, I saw a familiar profile, complete with the hair, between the words Stop Bigotry. So, we can add bigots and non-bigots to the polarized and polarizing list. And, what is more, we know, each one of us knows, which is which. We know, we are proud to know, the difference between the wheat and the weeds. How do we react to this reality of our field, our world?

The slaves in the parable know this difference, too. And they go to the householder and offer to uproot the weeds, because they know which is which. But the householder says, “No, for in gathering the weeds you would uproot the wheat along with them. Let both of them grow together.”[2]

The designations of wheat and weeds, and the remedies each of us has for the field in which we live, all have been put on hold by this parable. They have been put on hold by God’s preference for patience and tolerance.

The wheat can grow, and the weeds can grow, because uprooting one could damage the other. Our role in the world is to grow as best we know how, recognizing that there is a householder who, at the last, will preserve the wheat.

In the past, I have named this patience and this tolerance to be letting God be God. And letting God be God is hard, I know. I would rather step in and make sure things were put right. But stepping in that way would compromise God, and that would be to my way of thinking but maybe not to your way of thinking. And beyond that, stepping in may not be to God’s way of thinking.

And so, the Parable of the Wheat and the Weeds is a cautionary tale reminding us that though we have been made in God’s image, we simply have no business in remaking the world in our image. What if we mistake wheat for a weed?

[1] Saint Matthew 13:38.

[2] Saint Matthew 13:29-30a.